Doug

Gonaive is a little village to the northwest of Port au Prince, a two and a half hour drive. I have not been here since my first trip to Haiti, October 2009, prior to the earthquake. Memories tug at me as we drive to the village of Saint Marc and drive on further up. I remember a poor village, where many children were malnourished . I remember being relieved when I saw Gonaive has a school. A school means schoolchildren get to eat. This village has not been visited by a mission team since our last time here.

We arrive. It is a forgotten village, a poor village, and I hope things are not too desperate here. Living in this village is like careening down a twisty mountain road, mere inches from going over the edge, and there is nothing to stop the fall, no guardrail.

Guesly

Erika returns with her assessment: The patient’s cervix is 7 to 8 cm dilated and almost completely thinned out. This is her third pregnancy. I look around me in this dark cinder block church with primitive wiring for electricity powered by a generator. The roof is corrugated aluminum sheet held with sparse wooden trusses The church is dim with light creeping in from a few well crafted fenestrated cinder blocks. The floor is a mixture of dirt and large sharp rocks which remind me where I am with every step. I think we might have to deliver her here. I make my way to an unfinished alcove behind the altar. It is the only area that is semi-private.. As I enter the room, I see a women in her late 20’s to early 30’s lying on a oversize trash bag which covers most of her trunk on the unforgiving rock. Her feet and sandals are darkened to the color of the dirt; her dress is pulled up over her belly. She moans with each contraction. It has been almost five years since I finished residency , I know delivering children is far beyond the scope of medicine I want to practice. Haiti does not care about my preferences and brings unexpected and inconvenient challenges with each mission trip. This is Erika’s second trip to Haiti and already she knows to expect the unexpected. But it is not so much the unexpected that is the problem. The problem is that there is no system equipped to handle the unexpected. If we, the intermittent and temporary mission teams, are the best response, then the system is broken. To change the high morality and morbidity of newborns and their mothers, the whole system must be fixed.

“Dokte, dokte- nou gen yon maman ke vini avek yon tibebe ke mouri nan vant li!”* I am sitting in the dining room playing a game called Qurko with my sister Sabine and Ouyse, a family resident from Kansas City, when I hear the call of one of the translators. I spring to my feet, and grab Cory Miller, an OB-gyn resident from Columbia Missouri. We rush downstairs to find a women in the operating room, lying on the surgical table. At first glance, I can tell something is not right, something beyond the moans with every contraction.. Her appearance is off. Her face was swollen like someone suffering an allergic reaction, but I know that is not the case. The swelling is also encompassing her arms and legs. She is lethargic and remains still until a contraction stirs her to thrash and moan again. I asked her name and age. In Creole, she tells me she is 19 years old and 8 months pregnant. She continues to answer questions in a soft, anguished voice as I translate for Cory who does not speak Creole. We both notice her husband is not present in the room but waits outside in the lobby area. She explains that she lives in the mountains past a place called Fond Varette. As she speaks, I start to understand how difficult her journey has been. Fond Varette is a mountain where we often hold mobile clinics. The terrain to the small village is very unforgiving and painful. It has no mercy for people or vehicles. The road is very dusty because it runs along a dry riverbed. It has ruts due to erosion from repeated heavy rainfall and haphazard road construction. The drive itself is a slow climb on a road built to handle one vehicle but often carries three to four lanes of traffic. When I ride on it, I always hope I am on the vehicle closest to the mountain, not the vehicle on the outside where the edge falls off to a several thousand foot drop. No guardrail will arrest the fall. Traveling that road in the middle of the night in the back of a tap-tap is terrifying to imagine, even for someone who is not eight months pregnant. As I think this, she tells us her story.

On Friday, the mother developed a fever and noticed ther baby was not moving. The next day, she developed sudden abdominal pain,causing her to double over, and she began bleeding from her vagina. Her husband urged her to go to the hospital. This is their first baby; they just married a year ago. They went to see a local midwife, but she refused to see the mother. They waited. By Monday, the pain and contractions are unbearable. They make the harrowing trip down the mountain.

After Cory and I both assess her it was clear there is no fetal heart beat. Her unborn child will not have a chance to fight for his or her life. Our minds turn to treating her current potentially fatal medical condition. She arrives with severely elevated blood pressure and swelling. She had a condition called preeclampsia, and if it is not treated she could rapidly develop eclampsia which could endanger her life. Preeclampsia is a hypertensive syndrome that occurs in pregnant women after 20 weeks gestation consisting of new onset, persistent elevated blood pressure. Eclampsia is the progression of the disease process with initiation of seizure. I defer to Cory’s expertise concerning the treatment and management of this condition. My concern is whether an emergency c-section will be needed to remove the dead baby in her belly. Cory and I decide to awaken the surgical crew and Dr. Higgins, the general surgeon who practices in Kansas City. Dr. Cory and Dr. Higgins perform the surgery. Once the baby is delivered, it is clear he has not been alive for some time. Around the placenta is old clotted blood. The placenta has separated prematurely from the uterus, a condition called placental abruption. This condition is rapidly lethal for the baby and very dangerous for the mother. Her condition is not uncommon, and if recognized and treated, the risk to mother and baby can be minimized. That requires good pre-natal care which the patient failed to get because of location she lives, the scarcity of physicians, the lack of education, and a health system that only provides care to those who could afford to pay. Since eighty percent of Haitians are poor, all those pieces rarely fall into place, and this outcome is all too common.

Doug

We name the baby Esau. It was clear from the moment he is handed to me his earthly journey was over before his mother ever came down from the mountain. He is tiny, less than 5 pounds. He is limp. He has lividity in his skin, the blood pooling due to gravity after death. I listen to his heart, and this formality confirms what I already know. I wonder if he could have been saved in the US. I don’t know. I certainly have seen babies stillborn at my hospital. But the survival rate of a child living until the age of two is fifty times worse in Haiti than the US. Mothers are 100 times more likely to die in childbirth.

We pray over Esau, welcoming him into this world, and wishing him well on his journey out of it. That night he is buried next to David.

Guesly

We cannot have the baby here. I think this as I look around the rural Haitian church. There are no sterile instruments, only dental floss to tie off the umbilical cord. My mind drifts back to only eight hours ago when we had to tell a 19 year old mother that not only was her baby dead, but we had to have an emergency operation. We cannot deliver here. Doug, our pediatrician, concurs with this. I realize the pain of delivery would be far from the only pain she would suffer with no comfortable place for her to lay, increased risk for infection, and the possibility of unforeseen complications which could even lead to death of her unborn baby. I think if we were closer, I would take her to Fond Parisian where we have trained staff and emergency equipment. Even in Haiti, we can have a situation where the likelihood of survival can be improved, but we are several hours from the hospital, None of us did think she would make it. I can imagine her delivering driving eighty miles per hour in a street packed with cars, motorbikes, bicycles, and pedestrians. Fortunately, we are told of a location five minutes drive away with a trained midwife. clinic. Without a second thought I tell Erica to get the mother, and she and Sabine drive her to that clinic.

Haiti must change in this modern age. It cannot continue to operate in a fashion that does not respect or treasure human life.

Doug

Gonaive is better than I had hoped. We have a long, but good day. There are two or three very ill people, and we do what we can for them. In general, these people are managing. As Guesly says, it is hard to appreciate that Haiti, as a governmental system, is living up to its role as protector of the people, to provide that safety for those weak, in danger, and at risk. It is indeed hard to see where there is enough value given to human life. For now, though, this forgotten village is continuing on its road, on the edge, without a guardrail.

*"We have a mother that came with a baby that died in the womb"

Search This Blog

Monday, November 14, 2011

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Monday, November 07, 2011 -- Ghosts of Port au Prince

Doug

Today we travel to a church in Port au Prince for a mobile clinic. Guesly and I accompany a medical team from Bethel Church, in Washington. This is the first time I’ve actually worked in Port au Prince since the January 2010 trip, when we set up clinic at a school where the main building had collapsed, entombing close to 30 students. We worked there in the eerie wake of those lost but not quite gone children. Now we arrive at a resurrection of sorts. This church building was destroyed in the quake. It is, as are so many buildings in Port au Prince, in the process of being rebuilt. In this shell, I wonder, how many were lost? What ghosts still linger? I’m not talking about the fantastic, tortured shades of cinema. It’s the everyday ghosts. The memories that intrude. The old places, down in rubble. The rubble now cleared. The faces still fresh in the mind that will never be seen again. Every one a husband, a grandmother, a sister, a child. So many lost, so much loss. The scars that are everywhere--on the land, on the buildings, on the bodies. I still can see the haunted look on the faces of everyone we passed in the days after the quake. When I talk to survivors, “Where were you when it happened?” the look returns. The ghosts still just beneath the surface. Guesly and I will see that today.

Guesly

“Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” The old lady sits across from me in a makeshift church made of cinder block. Steel rebar sprouts from the ceiling and walls. This is our mobile clinic, this church where privacy is gives way to the children peeking through the many cracks in the walls. Again the patient says in “Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” Creole. Her statement brings me back to reality, the reality of being in Haiti again for another mission trip. This is the first time I am back in Port au Prince, working in a clinic since we were here after the earthquake. The images from the earthquake remain vividly in my mind, through the images from the TV screen and in images from my own memory after leading a medical team to help with relief efforts. I remember all the rubble from the crumbled buildings. I remember the sheer number of buildings destroyed, and I remember the sense of hopelessness in the Haitian people’s faces. Today, I see little remaining of the rubble. I see more normal activity, the hustle and bustle of life in Haiti, which would be considered completely chaotic for anybody living in the States or elsewhere but is welcome and comfortable here. After a few seconds that felt like several hours lost in my thoughts, I ask “Ki kote ou gen dolor, madam?” “Where do you hurt?” She explains in Creole that every day she has pain, tingling, and numbness down her left leg. She describes pain that has stolen her sleep and that grows worse below her knee. She says her pain started over a year and a half ago. As she speaks I begin to think of a laundry list of questions I need to ask to find exactly the source of her pain. When she is done talking, she patiently answers my questions as she sits, well dressed in her Sunday best, a white handkerchief wrapped over her head. Her facial expression appears fatigued like a person who has lived several hundred Sundays and has yielded to the hardship, poverty, gifts, and hopelessness that comes with being born in Haiti. .

After I have asked my questions to satisfy my need for information and develop my differential, I begin to examine her and the suspect area. Finally, I kindly ask her to lift her dress enough so I can see her leg and knee. What I see catches me completely by surprise. I should have thought of this in my differential, but my observation of her started with seeing her walk through the court yard with a considerable amount of large rocks strewn about like a river bed. Even I had difficulty maneuvering without spraining an ankle, but from what I saw she had no trouble walking. She was slow, but that is not uncommon for her age. I recall this as I am staring at what has appeared from under her dress. It is not her own leg. It looks completely different than her other one, and I realize it is artificial, prosthetic.

Her voce soft and gentle, she begins to talk about what people call in Haiti “the event.” ”When the event occurred on January 12, 2010, I was in my house when suddenly it shook and I fell, and the house fell, and I was trapped underneath the rubble…” She smiles to reassure me, but I see through it that she has lost more then her leg Her eyes glaze, and I sense that I have brought back a flood of painful memories that she would rather keep hidden deep in her subconscious as her left leg was hidden underneath her dress. As we talk, she explains that her lower leg was crushed, it was removed, gone, but some days she feels tingling and pain all the way down her leg to the ankle as if it was still there and had not been “cut off.” I place my head down for a second, again reliving the memories of my time spent after the earthquake.

I remember a little girl I saw, just 11 years old, whose father had argued that he did not want “ them” to cut his daughter's legs off so that she would never be whole. “Them” referred to the various foreign doctors that came to help with earthquake relief efforts whose efforts to saves lives meant amputating limbs from crush victims. The Haitian people equated seeing the foreign doctors to losing arms and legs. They had real fears in that time that seeing “them” would destroy their wholeness. The 11 year old’s leg was leg became infected after being crushed, and there were concerns that the infection could be make it way into her blood stream, which meant she lost her leg or lost her life. Either decision came with a terrible price. In the end the earthquake cost the daughter her leg, but not the family their daughter. I know this woman now sitting in front of me must have faced the same awful choice.

I explain to the patient she is experiencing what is called phantom pain. This could be a syndrome in itself as many people who had limbs amputated suffer from these symptoms. Patients often feel as though their leg is still present, causing them pain to the point of being debilitating. Phantom pain can be helped if the patient is placed on medication that decreases the pain signals generated from damaged nerves. She appears to be satisfied with my explanation and wonder about the medication. I explained to her that unfortunately I did not carry that medication with me and she would need to travel to Fond Parisen where the mission hospital and clinic has a limited amount. After some further discussion, I give her prescription for Tylenol as I did not have any narcotic with me and it is hard to find in Haiti. She says a polite thank you “doc” , and promises to try to go to the hospital in Fond. Fond Parisen is the home of the mission hospital I travel to while in Haiti. It is about an hour from the church in Port au Prince but could be 4 to 5 hours with traffic.

After my encounter I begin to think how far in time it seems since I was in Haiti to help treat earthquake victims, yet how is seems like yesterday to the Haitian people who were afflicted and who continue to seek treatment for their injures. I wonder if that little girl is suffering from similar symptoms and if she will seek treatment as my patient today. Already the world has forgotten or is forgetting about Haiti. The news is always looking for the next sensational story. But the people in Haiti cannot forget. They continue to suffer. Their lives are forever changed. The need for healing will surpass my time and my generation. Do not forget about Haiti as the need for help is just beginning.

Doug:

So much is better. So much has healed, but the scars, the ghosts persist. Phantom limb may be a good way to think of it. It’s as if the whole body of the people of Port au Prince has lost a limb. The body moves, the people move about and get along the best they can, but they still feel it, every day. They feel them, the ones they lost, the ones we lost, every day. It’s been a good, tiring clinic. We head back to Fond Parisien to regroup and restock, and leave the city to its ghosts.

Port au Prince, November 7, 2011

Today we travel to a church in Port au Prince for a mobile clinic. Guesly and I accompany a medical team from Bethel Church, in Washington. This is the first time I’ve actually worked in Port au Prince since the January 2010 trip, when we set up clinic at a school where the main building had collapsed, entombing close to 30 students. We worked there in the eerie wake of those lost but not quite gone children. Now we arrive at a resurrection of sorts. This church building was destroyed in the quake. It is, as are so many buildings in Port au Prince, in the process of being rebuilt. In this shell, I wonder, how many were lost? What ghosts still linger? I’m not talking about the fantastic, tortured shades of cinema. It’s the everyday ghosts. The memories that intrude. The old places, down in rubble. The rubble now cleared. The faces still fresh in the mind that will never be seen again. Every one a husband, a grandmother, a sister, a child. So many lost, so much loss. The scars that are everywhere--on the land, on the buildings, on the bodies. I still can see the haunted look on the faces of everyone we passed in the days after the quake. When I talk to survivors, “Where were you when it happened?” the look returns. The ghosts still just beneath the surface. Guesly and I will see that today.

Guesly

“Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” The old lady sits across from me in a makeshift church made of cinder block. Steel rebar sprouts from the ceiling and walls. This is our mobile clinic, this church where privacy is gives way to the children peeking through the many cracks in the walls. Again the patient says in “Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” Creole. Her statement brings me back to reality, the reality of being in Haiti again for another mission trip. This is the first time I am back in Port au Prince, working in a clinic since we were here after the earthquake. The images from the earthquake remain vividly in my mind, through the images from the TV screen and in images from my own memory after leading a medical team to help with relief efforts. I remember all the rubble from the crumbled buildings. I remember the sheer number of buildings destroyed, and I remember the sense of hopelessness in the Haitian people’s faces. Today, I see little remaining of the rubble. I see more normal activity, the hustle and bustle of life in Haiti, which would be considered completely chaotic for anybody living in the States or elsewhere but is welcome and comfortable here. After a few seconds that felt like several hours lost in my thoughts, I ask “Ki kote ou gen dolor, madam?” “Where do you hurt?” She explains in Creole that every day she has pain, tingling, and numbness down her left leg. She describes pain that has stolen her sleep and that grows worse below her knee. She says her pain started over a year and a half ago. As she speaks I begin to think of a laundry list of questions I need to ask to find exactly the source of her pain. When she is done talking, she patiently answers my questions as she sits, well dressed in her Sunday best, a white handkerchief wrapped over her head. Her facial expression appears fatigued like a person who has lived several hundred Sundays and has yielded to the hardship, poverty, gifts, and hopelessness that comes with being born in Haiti. .

After I have asked my questions to satisfy my need for information and develop my differential, I begin to examine her and the suspect area. Finally, I kindly ask her to lift her dress enough so I can see her leg and knee. What I see catches me completely by surprise. I should have thought of this in my differential, but my observation of her started with seeing her walk through the court yard with a considerable amount of large rocks strewn about like a river bed. Even I had difficulty maneuvering without spraining an ankle, but from what I saw she had no trouble walking. She was slow, but that is not uncommon for her age. I recall this as I am staring at what has appeared from under her dress. It is not her own leg. It looks completely different than her other one, and I realize it is artificial, prosthetic.

Her voce soft and gentle, she begins to talk about what people call in Haiti “the event.” ”When the event occurred on January 12, 2010, I was in my house when suddenly it shook and I fell, and the house fell, and I was trapped underneath the rubble…” She smiles to reassure me, but I see through it that she has lost more then her leg Her eyes glaze, and I sense that I have brought back a flood of painful memories that she would rather keep hidden deep in her subconscious as her left leg was hidden underneath her dress. As we talk, she explains that her lower leg was crushed, it was removed, gone, but some days she feels tingling and pain all the way down her leg to the ankle as if it was still there and had not been “cut off.” I place my head down for a second, again reliving the memories of my time spent after the earthquake.

I remember a little girl I saw, just 11 years old, whose father had argued that he did not want “ them” to cut his daughter's legs off so that she would never be whole. “Them” referred to the various foreign doctors that came to help with earthquake relief efforts whose efforts to saves lives meant amputating limbs from crush victims. The Haitian people equated seeing the foreign doctors to losing arms and legs. They had real fears in that time that seeing “them” would destroy their wholeness. The 11 year old’s leg was leg became infected after being crushed, and there were concerns that the infection could be make it way into her blood stream, which meant she lost her leg or lost her life. Either decision came with a terrible price. In the end the earthquake cost the daughter her leg, but not the family their daughter. I know this woman now sitting in front of me must have faced the same awful choice.

I explain to the patient she is experiencing what is called phantom pain. This could be a syndrome in itself as many people who had limbs amputated suffer from these symptoms. Patients often feel as though their leg is still present, causing them pain to the point of being debilitating. Phantom pain can be helped if the patient is placed on medication that decreases the pain signals generated from damaged nerves. She appears to be satisfied with my explanation and wonder about the medication. I explained to her that unfortunately I did not carry that medication with me and she would need to travel to Fond Parisen where the mission hospital and clinic has a limited amount. After some further discussion, I give her prescription for Tylenol as I did not have any narcotic with me and it is hard to find in Haiti. She says a polite thank you “doc” , and promises to try to go to the hospital in Fond. Fond Parisen is the home of the mission hospital I travel to while in Haiti. It is about an hour from the church in Port au Prince but could be 4 to 5 hours with traffic.

After my encounter I begin to think how far in time it seems since I was in Haiti to help treat earthquake victims, yet how is seems like yesterday to the Haitian people who were afflicted and who continue to seek treatment for their injures. I wonder if that little girl is suffering from similar symptoms and if she will seek treatment as my patient today. Already the world has forgotten or is forgetting about Haiti. The news is always looking for the next sensational story. But the people in Haiti cannot forget. They continue to suffer. Their lives are forever changed. The need for healing will surpass my time and my generation. Do not forget about Haiti as the need for help is just beginning.

Doug:

So much is better. So much has healed, but the scars, the ghosts persist. Phantom limb may be a good way to think of it. It’s as if the whole body of the people of Port au Prince has lost a limb. The body moves, the people move about and get along the best they can, but they still feel it, every day. They feel them, the ones they lost, the ones we lost, every day. It’s been a good, tiring clinic. We head back to Fond Parisien to regroup and restock, and leave the city to its ghosts.

Port au Prince, November 7, 2011

Monday, November 7, 2011

Landed and (hopefully) Grounded

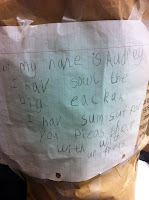

We arrive Sunday after a long travel day. Late, we are delayed in Miami, we land in darkness. We breeze through customs. I don't know if we are getting better at this, the wheels are used to being well greased, or my tolerance for the chaos is just higher. All the bags make it. Outside the airport, making the way to the vans, the darkness is a new experience. Port au Prince airport at night is eerie and vaguely threatening. I shrug it off, I wonder what I would think if it was my first time here. /the trip to Fond Parisien is quiet. I have time to think about the strange flow of events that have brought me back here again. I keep thinking back to an appointment I had last Thursday. It was a routine well check wit my patient Audrey, an 8 year old who I have seen since birth. She is delighted to see me, and she has brought a paper grocery bag with her. In it are many treasures: stuffed animals, books, bubbles, two boxes of macaroni and cheese, and various other small things that are important to an eight year old. She has printed a big note

"My name is Audrey. I have saw the Earthquake. I have some stuff for you. Please share with your friends." Almost two years ago, she was touched by the plight of the people of Haiti. At 6, she thought "what would I want, if I were in Haiti." So she gathered the things that make a six year old happy. And she saved them. She also collected some money and saved that. She was looking for some way to get it to Haitian children. She finally realized that I was going back to Haiti and brought it in to her appointment. I could barely read it in front of her without tears welling up. Just thinking about it now, I feel the same way. It's that purity of generosity, of a will to help, that is the wave that I have ridden, once again, to this place.

I raised a lot of money after the earthquake, and I've spent nearly all of it funding 5 mission trips, and it's not because I am a good fundraiser. I stink at it. I have a hard time asking people for money, so the money that has been donated came from people like Audrey, who still have Haiti on their hearts, even nearly two years later. I just had a family send me a check whose father had been a missionary to Haiti, and he had always wanted to share the experience with his family, but he dies before he could. So they are sending me along in his memory. In a way, then, he is with me. All the team members who have shared this mission previously are with me, as well.

So thank you, Audrey, and thank you everyone who continues to support us despite my ineptness in asking for it. I believe in what we are doing. The people who come with us are the wave riders, and you are the wave. This week, I want to make it worth it. I want to use Audrey's bag and everything in it in the best way possible.

Doug 11/6/2011

"My name is Audrey. I have saw the Earthquake. I have some stuff for you. Please share with your friends." Almost two years ago, she was touched by the plight of the people of Haiti. At 6, she thought "what would I want, if I were in Haiti." So she gathered the things that make a six year old happy. And she saved them. She also collected some money and saved that. She was looking for some way to get it to Haitian children. She finally realized that I was going back to Haiti and brought it in to her appointment. I could barely read it in front of her without tears welling up. Just thinking about it now, I feel the same way. It's that purity of generosity, of a will to help, that is the wave that I have ridden, once again, to this place.

I raised a lot of money after the earthquake, and I've spent nearly all of it funding 5 mission trips, and it's not because I am a good fundraiser. I stink at it. I have a hard time asking people for money, so the money that has been donated came from people like Audrey, who still have Haiti on their hearts, even nearly two years later. I just had a family send me a check whose father had been a missionary to Haiti, and he had always wanted to share the experience with his family, but he dies before he could. So they are sending me along in his memory. In a way, then, he is with me. All the team members who have shared this mission previously are with me, as well.

So thank you, Audrey, and thank you everyone who continues to support us despite my ineptness in asking for it. I believe in what we are doing. The people who come with us are the wave riders, and you are the wave. This week, I want to make it worth it. I want to use Audrey's bag and everything in it in the best way possible.

Doug 11/6/2011

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Why We Keep Going

We are planning our next trip to Haiti, from Nov. 6-12. It is such a whirlwind. We need so much. We have to find medications and supplies. We need money. We need nurses (especially pediatric nurses). I find it amazing that this will be Ke Nou's (and Missouri Haitian Relief Fund's) fifth trip.

What keeps us going? Why do we keep going back?

On the one hand, that answer is easy: the need is so great. The people we serve don't stop getting ill once the cameras are no longer trained on them or their country. The earthquake was terrible, but the need was tremendous before the quake, and it continues as the rubble still is being cleared. We see that every time we go. We save lives on every trip.

The second answer is that we are trying to build something: Each time we go, we want to leave the clinic and hospital in Fond Parisien more capable of responding to the need. Also, with each trip, hopefully one more team member gets the bug to return to serve again.

Third, it is personal: to me once I've seen the look in one child's eyes, I cannot unsee it. Once I have opened my heart to these people and this place, it always is with me. I really have no choice. I need to go back.

Here's the thing: We don't do it for thanks. We don't do it for recognition. We go because our lives don't make sense if we don't go. We do it because when we are there, in this desperate place, all the pieces come together, and we know we are exactly where we were meant to be, doing what we were made to do. We are alive.

People here in the States will come up to me and thank me for what I am doing. I understand why they do. I recognize that I am doing something that many are unable or unwilling to do, and people recognize that our work is needed, but I always feel a little awkward when I hear the "Thank You" or when someone is trying to tell me what a great person I am for going on mission trips.

Thanking me for going on mission trips is like thanking me for breathing oxygen. I do it because I have to. Ask anyone who truly has it in their heart, and they will tell you the same. Praise for what I do, in a strange way, makes me feel more humble. I often tell people, in reply, that I am only a vessel. I only play a very small part, doing the work that has been given me. That's all I want to be. I don't need this to feed my ego. In fact, I have seen, unfortunately, people for whom it is one big ego trip. They are tourists. That is not what I want to be. I want my work to mean something. My name and face can disappear in the wake of what I have done.

And yet....it does make me happy when people see that our work is worthwhile. Because the more people are behind us, the greater chance that someone will be moved to help out: with money, with supplies, with volunteering...anything that keeps this machine going. And we need it. Fundraising was easy after the earthquake. Now we are operating with less and less of a cushion. So if you feel gratitude for what we have done, recognize that you do not have to be a spectator. You can share in our mission. Maybe you can join us physically in a future mission. Maybe you can join us by sharing financially. Any gift can extend our common reach and can allow the mission to live on. Always, we are working so that we can continue to work. And we will continue to keep going. Because we have to. It is how we are made, why we were made.

Doug

Ke Nou Haiti

c/o Missouri Haitian Relief Fund

PO Box 873

Jefferson City, MO 65102

What keeps us going? Why do we keep going back?

On the one hand, that answer is easy: the need is so great. The people we serve don't stop getting ill once the cameras are no longer trained on them or their country. The earthquake was terrible, but the need was tremendous before the quake, and it continues as the rubble still is being cleared. We see that every time we go. We save lives on every trip.

The second answer is that we are trying to build something: Each time we go, we want to leave the clinic and hospital in Fond Parisien more capable of responding to the need. Also, with each trip, hopefully one more team member gets the bug to return to serve again.

Third, it is personal: to me once I've seen the look in one child's eyes, I cannot unsee it. Once I have opened my heart to these people and this place, it always is with me. I really have no choice. I need to go back.

Here's the thing: We don't do it for thanks. We don't do it for recognition. We go because our lives don't make sense if we don't go. We do it because when we are there, in this desperate place, all the pieces come together, and we know we are exactly where we were meant to be, doing what we were made to do. We are alive.

People here in the States will come up to me and thank me for what I am doing. I understand why they do. I recognize that I am doing something that many are unable or unwilling to do, and people recognize that our work is needed, but I always feel a little awkward when I hear the "Thank You" or when someone is trying to tell me what a great person I am for going on mission trips.

Thanking me for going on mission trips is like thanking me for breathing oxygen. I do it because I have to. Ask anyone who truly has it in their heart, and they will tell you the same. Praise for what I do, in a strange way, makes me feel more humble. I often tell people, in reply, that I am only a vessel. I only play a very small part, doing the work that has been given me. That's all I want to be. I don't need this to feed my ego. In fact, I have seen, unfortunately, people for whom it is one big ego trip. They are tourists. That is not what I want to be. I want my work to mean something. My name and face can disappear in the wake of what I have done.

And yet....it does make me happy when people see that our work is worthwhile. Because the more people are behind us, the greater chance that someone will be moved to help out: with money, with supplies, with volunteering...anything that keeps this machine going. And we need it. Fundraising was easy after the earthquake. Now we are operating with less and less of a cushion. So if you feel gratitude for what we have done, recognize that you do not have to be a spectator. You can share in our mission. Maybe you can join us physically in a future mission. Maybe you can join us by sharing financially. Any gift can extend our common reach and can allow the mission to live on. Always, we are working so that we can continue to work. And we will continue to keep going. Because we have to. It is how we are made, why we were made.

Doug

Ke Nou Haiti

c/o Missouri Haitian Relief Fund

PO Box 873

Jefferson City, MO 65102

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Closure--Melinda Dessieux

I can hardly sleep the night before the flight. It could be from excitement (or the fact that I am having a hard time keeping anything down), but after 23 years have passed, I am finally going to the place my family calls home. After watching Haiti Haiti

I am home the moment I step off the airplane.

I never thought I would enjoy rubbing little children down with permethrin cream, take pleasure in instructing a mom on how to use an inhaler with her son, or use juice (pedialyte) to persuade a 6 year old into taking a worm pill……but I do. I know that some of the patients that were seen at the off-site medical clinics would not have had any medical care or access to medical care for a while. Even the medical care provided at the clinics is limited by the amount of resources available, yet that is never an obstacle. Everyone on the trip has a ‘get it done’ mind set: From creating a makeshift pharmacy to using a car as the power source for a nebulizer.

The day before we leave, we are able to go to the orphanage that is down the street from the mission, and I have so much fun there. The children are so polite, and I fall in love with a 7 month old named Gigi. Her mother passed away during birth. Her grandmother, unable to take care of her, gave her to the mission because she knew that Gigi would be well cared for. Despite the situation she was born into, Gigi is the happiest baby I have ever met. She is loved and adored by everyone she makes eye contact with, especially me.

I did not expect to be touched during this trip, in my mind I thought I knew everything there was to being Haitian…Man, was I wrong. Many of us wake up every day and take for granted the blessings God has set before us. Prior to this trip I was unsure about what I wanted out of life--I definitely would be fibbing if I said I was deliberately searching for the answers to my life--I can honestly say, though, that this trip has inspired me to redirect my focus to the simple things in life. Simple things like teaching a child patty cake or dancing on a roof top surrounded by mountains and a lake….or waking up to a guy praising the Lord on a bullhorn (okay maybe that wasn’t simple). This country is absolutely beautiful and amazing. Since I have been back to the States I feel like a foreigner.

I love my experience and I hope everyone experiences something like this at least twice in their lifetime.

The time and money that I donated with Ke Nou was nominal in comparison to what I had the opportunity to experience and the lifelong friends I acquired. If there is one thing I regret, it is that I did not have the ability to do and give more while I was there. Ke Nou, thank you for a truly enlightening experience.

Melinda Dessieux

Saturday, July 16, 2011

Reflections--Jeanne Boudreau

Myriad emotions sweep over me upon returning home on Sunday. I am happy to be safely home enjoying the simple pleasures of clean water, hot shower, cool air and my own bed. I have put my life on hold for an incredible week in Haiti

My expectations going into the trip are open ended and influenced by what I have seen on TV. I am not prepared for what I see in Port-au-Prince

Once we leave the city, I am surprised by the vast expanse of land and the beauty of the countryside with the mountains, lake and ocean. I observe many contrasts as we journey through the land. There is the treeless side of the mountains vs. the forested side of the mountains. I see small villages with cinder block houses and then elegant homes in the hills. The tent cities cluster in the midst of affluent areas. There is so much evidence of extreme poverty everywhere, but somehow people have cell phones, even in the poorest of villages. I feel anger at those people who have acquired wealth at the expense of the poor people and the corrupt government unable to help their people. To me, it seems so hopeless. I wonder how the Haitian people feel about the situation.

The highlight of my week is my experience with the Haitian children. As a non medical person my responsibility is to oversee

The highlight of my week is my experience with the Haitian children. As a non medical person my responsibility is to oversee The translators and some of the medical team join me and my 2 granddaughters for our first session. We journey up a rocky winding narrow road to a remote farming village in the mountains. These villagers make their living growing vegetable in terraced gardens on the steep hillsides. The mountain side has the appearance of a patchwork quilt.

We are greeted by about 40 children on the steps of the church. I think to myself, this will be a piece of cake. This all changes very quickly as word of our arrival spreads rapidly as we are setting up.

The children pour though the doorway and make their way to the wooden benches. They are amazingly orderly. The translators assist me in telling a bible story. They sing one of their songs to us and I think I will teach them “Jesus Loves Me”. To my surprise they already know it and sing it to us. I do teach them one song. We pass out coloring pages of various Christian symbols and one crayon to each child.

The children pour though the doorway and make their way to the wooden benches. They are amazingly orderly. The translators assist me in telling a bible story. They sing one of their songs to us and I think I will teach them “Jesus Loves Me”. To my surprise they already know it and sing it to us. I do teach them one song. We pass out coloring pages of various Christian symbols and one crayon to each child. They all share their colors and produce some very colorful pictures. We also make a large circle and play pass the “hot potato” with a soccer ball. Everyone loves the game and do not want to quit. We leave the first day feeling we had a successful day but began making plans to meet the challenges of the second session.

Once again we made the journey up the mountain. This time we are better organized. We keep the children outside until we have set up separate work stations in the church. We divide the children up by age groups and let each group in one at a time. They are very orderly and waiting patiently. Each person on the team is assigned to a group and does some simple crafts with each group.

The last of the groups consists of about 40 older children, predominately young boys, who I take to an adjacent building. I have to quickly come up with an activity for my group. Thank goodness I brought lots of tissue paper and pipe cleaners, string and balloons. Believe it or not these children enjoy making folded tissue flowers. They also have fun playing “Stomp the balloon”. Each child blows up a balloon and ties it around his ankle. We allow 10 people to play at a time. I join the group with another team member for the first round. Thanks goodness my balloon is popped quickly before I got hurt. It was a rambunctious group. The translators and the pastor do a good job of controlling the children.

The last of the groups consists of about 40 older children, predominately young boys, who I take to an adjacent building. I have to quickly come up with an activity for my group. Thank goodness I brought lots of tissue paper and pipe cleaners, string and balloons. Believe it or not these children enjoy making folded tissue flowers. They also have fun playing “Stomp the balloon”. Each child blows up a balloon and ties it around his ankle. We allow 10 people to play at a time. I join the group with another team member for the first round. Thanks goodness my balloon is popped quickly before I got hurt. It was a rambunctious group. The translators and the pastor do a good job of controlling the children.  After all activities are over, we gather in the church. One of the translators is a great singer and leads the group in song. We offer a parting prayer and leave. The women of the village have prepared roasted fresh corn for all of us. As we are leaving, I felt the presence of God in this beautiful place. His spirit has truly been with us all during these 2 days in the mountains of

After all activities are over, we gather in the church. One of the translators is a great singer and leads the group in song. We offer a parting prayer and leave. The women of the village have prepared roasted fresh corn for all of us. As we are leaving, I felt the presence of God in this beautiful place. His spirit has truly been with us all during these 2 days in the mountains of Jeanne

Perspective--Lindsay Otto

One week has gone by since returning home from a trip I have always longed to be a part of: a mission trip to assist other people that are less fortunate than me. The medical mission trip to Haiti

I will never forget the scenes outside the bus window as we make our way to the Haitian Christian Mission (HCM) on our first day. Despite trash in the streets and tent cities, Haiti mountain view

We meet some children who are fortunate to belong to a family living in one of the new homes. This is our first contact with Haitian children. They are so happy! It is so hard for me to be unable to communicate with them through words due to the language barrier. But, I soon realize that a smile is universal – I smile at them and….. they smile back. Yes! It is great to see them smile!

We meet some children who are fortunate to belong to a family living in one of the new homes. This is our first contact with Haitian children. They are so happy! It is so hard for me to be unable to communicate with them through words due to the language barrier. But, I soon realize that a smile is universal – I smile at them and….. they smile back. Yes! It is great to see them smile!

Our first day of clinic goes well. I work in the pharmacy and quickly learn how to make-do with what we had for medications and supplies. I am able to interact with some of the patients by applying creams, giving shots, teaching mothers how to administer medications – all via assistance of our wonderful translators! I feel like we are positively impacting the lives of the patients we cared for, and I am uplifted and ready for the rest of the week!

The following days include another clinic at the mission and a mobile clinic at a church in a remote village.

Patients that appear 80 years old have never seen a doctor before and don’t know their birthdate. Farmers are farming crops on steep mountain-sides in the heat with no machinery, only manual labor and a shovel. A patient whose hand is severely cut does not even need pain medication after having to drive for 2 hours to get to a medical facility. Women (and sometimes men) are carrying loads of goods on their heads for miles and miles. Children are playing soccer and running on gravel with no shoes. These people are tough!

Patients that appear 80 years old have never seen a doctor before and don’t know their birthdate. Farmers are farming crops on steep mountain-sides in the heat with no machinery, only manual labor and a shovel. A patient whose hand is severely cut does not even need pain medication after having to drive for 2 hours to get to a medical facility. Women (and sometimes men) are carrying loads of goods on their heads for miles and miles. Children are playing soccer and running on gravel with no shoes. These people are tough!

Patients that appear 80 years old have never seen a doctor before and don’t know their birthdate. Farmers are farming crops on steep mountain-sides in the heat with no machinery, only manual labor and a shovel. A patient whose hand is severely cut does not even need pain medication after having to drive for 2 hours to get to a medical facility. Women (and sometimes men) are carrying loads of goods on their heads for miles and miles. Children are playing soccer and running on gravel with no shoes. These people are tough!

Patients that appear 80 years old have never seen a doctor before and don’t know their birthdate. Farmers are farming crops on steep mountain-sides in the heat with no machinery, only manual labor and a shovel. A patient whose hand is severely cut does not even need pain medication after having to drive for 2 hours to get to a medical facility. Women (and sometimes men) are carrying loads of goods on their heads for miles and miles. Children are playing soccer and running on gravel with no shoes. These people are tough!

But, when speaking with the people and talking with some of our translators, they voice they love their country and do not want to leave. I guess they are happy, they don’t know any different way of life besides what they are living now - survival.

I know that this trip has changed me. I will never forget these images, and anytime in the future when I am having a hard day or feeling down, I can count on these images to help me realize that there are people – not only in

I really believe that the HCM is a wonderful organization who is doing great things for the country of Haiti

Well, this is my first time blogging…..and I cannot believe that I have written this much already and still have so much I could say about this trip. I thank Ke Nou Haiti

Lindsay

Thursday, July 14, 2011

Change--Ashley Doyen

There are few experiences in life that you walk away from a completely changed person. The week I spent in Haiti is one of those experiences.

I was told to have no expectations and go on this trip with an open mind. I really have no idea what to expect, even if I try. I have never been out of the country prior to this trip.

As we walk out of the airport, Haiti hits me head on. The warm weather, the faint smell of charcoal in the air, car horns blasting, and most of all, the overwhelming number of people all speaking loudly in a language I don’t know. I instantly feel very vulnerable. Stimulation comes at me from every angle. It is all I can do to keep moving and not just sit down to take it all in.

The translators from Haitian Christian Mission are with us, guiding us toward the vans waiting to take us to the mission. I don’t know it at this point, but I will come to know the translators as my guardian angels acting not only as my link to this unfamiliar land, but also as protectors from any naive cultural mistake I might make.

We make it to the vans and pile in for what will be one of many very close, very bumpy rides. The ride through Port-au-Prince brings all the images from the television to life. The devastation left in the earthquakes wake is still present a year and a half later, not only in the piles of rubble, or tents pitched along the side of the road, but in the eyes of the people who watch us intently as we pass by. The sharp realization that I know nothing about loss and suffering compared to the people of this country tightens my chest and takes my breath away.

Already my perspective on the concerns of my everyday life has changed and I have been in Haiti for less than an hour. I start to worry I am in way over my head. I take a deep breath and start to pray. It is this technique that carries me though the rest of the week as I am pushed to grow in more ways than I thought possible.

The first day of clinic at the mission I am thrown into the role of triage nurse. I am physically shaking as I sit down with my translator and he calls the first name. Sure--it’s simple--take a set of vitals, talk with the person for a minute, get the chief complaint, and send them to the line to see the doctors. It sounds easy enough, but it is made complicated having to work through a translator.

I get to know and trust the translators I work with very quickly. They help catch the little things that could be the difference between diagnosing a cold or something more serious in the early stages.

It’s intimidating seeing so many people so quickly. The doctors only have limited time with each person. I feel responsible for getting them enough information to help them make a quick, yet accurate, diagnosis. I am still feeling a little timid when a man sits down with his 2 year old son. The boy is asleep, it’s very hot outside. Most of the kids, even if they are sleeping, stir or fuss when I take their temperatures. Not this little guy. He doesn’t move. I learn though my translator that he has had diarrhea and a fever for the last 5 days. I take his temperature, 104.6 degrees. I take them back to see Doug (the pediatrician with our team) right away. He is severely dehydrated and an IV is started in him right away. Maybe I know how to triage after all.

When we don’t have clinic at the mission, we head out to towns that have no means to seek out health care, so we take it to them.

The most memorable trip is our journey to Jacmel. This is a town way up in the mountains. It takes us over 5 hours to get there, so we are up and on the road before the sun comes up. I squeeze into the back seat squished in the space between the two actual seats making it 4 people in a row meant for 3. To say the road is bumpy is an understatement. All things considered, my heart is filled with joy as we drive through the beautiful Haitian land. The scenery is breathtaking.

It is uncomfortable conditions such as the back of the van that push me to dive in and get to know the members of the team really well. We bounce feelings and emotions off each other, share stories, laugh, cry, and before I know it I am developing friendships that will last long after the smell of burning trash leaves my nose.

I am honored with a first hand account of what it was like during the actual earthquake. A strong sense of pride for the country shows through in every story I hear.

By Friday we have really figured out how to work together well. It is our busiest, most successful day. It is a mobile clinic in a smaller farm village. We see almost 200 patients. They are all so kind and grateful. Really, looking back I don’t think I come in contact with one angry person all week long. Everyone, no matter their circumstances is just content.

I leave Haiti feeling very much the same. It is hard for me to leave. Sad goodbyes are said at the airport in Haiti, and again in Florida, and then again when we all part ways in Kansas City.

God called my heart to Haiti, and then He opened my eyes to all the opportunities to do good there. Words can simply not explain all that I learned, the ways that I grew, and the unforgettable memories, the confidence that I have gained and connections that I have made.

Haiti touched my heart. I long for the day I am able to return.

-Ashley

I was told to have no expectations and go on this trip with an open mind. I really have no idea what to expect, even if I try. I have never been out of the country prior to this trip.

As we walk out of the airport, Haiti hits me head on. The warm weather, the faint smell of charcoal in the air, car horns blasting, and most of all, the overwhelming number of people all speaking loudly in a language I don’t know. I instantly feel very vulnerable. Stimulation comes at me from every angle. It is all I can do to keep moving and not just sit down to take it all in.

The translators from Haitian Christian Mission are with us, guiding us toward the vans waiting to take us to the mission. I don’t know it at this point, but I will come to know the translators as my guardian angels acting not only as my link to this unfamiliar land, but also as protectors from any naive cultural mistake I might make.

We make it to the vans and pile in for what will be one of many very close, very bumpy rides. The ride through Port-au-Prince brings all the images from the television to life. The devastation left in the earthquakes wake is still present a year and a half later, not only in the piles of rubble, or tents pitched along the side of the road, but in the eyes of the people who watch us intently as we pass by. The sharp realization that I know nothing about loss and suffering compared to the people of this country tightens my chest and takes my breath away.

Already my perspective on the concerns of my everyday life has changed and I have been in Haiti for less than an hour. I start to worry I am in way over my head. I take a deep breath and start to pray. It is this technique that carries me though the rest of the week as I am pushed to grow in more ways than I thought possible.

The first day of clinic at the mission I am thrown into the role of triage nurse. I am physically shaking as I sit down with my translator and he calls the first name. Sure--it’s simple--take a set of vitals, talk with the person for a minute, get the chief complaint, and send them to the line to see the doctors. It sounds easy enough, but it is made complicated having to work through a translator.

I get to know and trust the translators I work with very quickly. They help catch the little things that could be the difference between diagnosing a cold or something more serious in the early stages.

It’s intimidating seeing so many people so quickly. The doctors only have limited time with each person. I feel responsible for getting them enough information to help them make a quick, yet accurate, diagnosis. I am still feeling a little timid when a man sits down with his 2 year old son. The boy is asleep, it’s very hot outside. Most of the kids, even if they are sleeping, stir or fuss when I take their temperatures. Not this little guy. He doesn’t move. I learn though my translator that he has had diarrhea and a fever for the last 5 days. I take his temperature, 104.6 degrees. I take them back to see Doug (the pediatrician with our team) right away. He is severely dehydrated and an IV is started in him right away. Maybe I know how to triage after all.

When we don’t have clinic at the mission, we head out to towns that have no means to seek out health care, so we take it to them.

The most memorable trip is our journey to Jacmel. This is a town way up in the mountains. It takes us over 5 hours to get there, so we are up and on the road before the sun comes up. I squeeze into the back seat squished in the space between the two actual seats making it 4 people in a row meant for 3. To say the road is bumpy is an understatement. All things considered, my heart is filled with joy as we drive through the beautiful Haitian land. The scenery is breathtaking.

It is uncomfortable conditions such as the back of the van that push me to dive in and get to know the members of the team really well. We bounce feelings and emotions off each other, share stories, laugh, cry, and before I know it I am developing friendships that will last long after the smell of burning trash leaves my nose.

|

| 4 people in a row meant for 3 |

By Friday we have really figured out how to work together well. It is our busiest, most successful day. It is a mobile clinic in a smaller farm village. We see almost 200 patients. They are all so kind and grateful. Really, looking back I don’t think I come in contact with one angry person all week long. Everyone, no matter their circumstances is just content.

I leave Haiti feeling very much the same. It is hard for me to leave. Sad goodbyes are said at the airport in Haiti, and again in Florida, and then again when we all part ways in Kansas City.

God called my heart to Haiti, and then He opened my eyes to all the opportunities to do good there. Words can simply not explain all that I learned, the ways that I grew, and the unforgettable memories, the confidence that I have gained and connections that I have made.

Haiti touched my heart. I long for the day I am able to return.

-Ashley

Monday, July 11, 2011

Friday, July 8th, Droulliard

Mobile clinics are our team's house calls, on a whole village. To prepare, we have to pack with us all the medicines that we think we might need, without packing the whole pharmacy. We leave behind our oxygen and lab and hospital beds. We can and do start IV's and give medicine IV or by injection.

We pack the night before, then get up early depending on where we are going. For Jacmel, that meant 4 am, for Droulliard, it's only about a 45 minute drive. Once we get to the village, we set up in the local church, which is the only place that has enough space to accommodate that many people. The pews are long wooden benches with backs. The village pastor sends people running for desks from the school for the triage nurses to interview and collect vitals. In triage, the nurses speak through their interpreters, asking about why they are here, what problems they have had in the past, and the other things that put the visit in context. We depend heavily on our interpreters. It is more than knowing how to speak both languages. When a patient says "Mwen gen grip la. (I have the flu.)", the translator has to understand and convey that she is not diagnosing herself with Influenza A, nor is she saying she has nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, which is what people in mid-Missouri mean by "the flu". She is saying that she has been having congestion and drainage in the nose. The translator has to pick up on that. They have to have enough medical knowledge to know what we are asking and enough facility with the language to get someone who has no medical knowledge at all to understand. It can get very frustrating, and they are not perfect, but they do a good job.

We rearrange the pew benches to make L shaped sections where patients sit in line waiting to see the provider, a physician (me or Gracia Nabhane) or nurse practioner (Sabine), and set up the pharmacy at the altar, blockaded by benches. The pharmacy itself is medications spread out, organized by kind with IV start kits and supplies for mixing things.

Once the patient slides towards me on the bench,

"Avanse. Avanse."

"Papye, Souplé. (Paper, Please)"

I skim it. "Li gen lafyèv? depi ki lè?"

The mother looks at my translator Max, clearly I have a horrible accent. Max says "Li gen lafyèv? depi ki lè? (She has a fever? For how long?)"

"Depi twa jou. (3 days). Epi li gen grip la. (and she has the flu (runny, stuffy nose)"

Me again "Eske li gen yon vant fè mal? (does she have a belly ache?)"

"Wi, li gen vant fè mal. (yes she has a belly ache) e li gen vè. (and she has worms.)"

"li te gen vè nan twalèt li? (She had worms in her poop?)"

"Wi, e (several words I don't understand)"

I look at Max. "She said she is coughing up the worms, also."

I examine the girl, telling her what I want her to do: "zòrèy,lòt zòrèy (ear, other ear), louvri bouch ou (open your mouth), respire, anko, anko, anko (breathe, again, again, again)" She has an ear infection, I prescribe an antibiotic, worm medicine, Advil for pain and fever, and chewable vitamins. Always vitamins. Even in this village, which looks relatively well-fed compared to where I have been. I write it on the paper.

"pote papye a nan famasi a. (take the paper to the pharmacy.)"

"Avanse. Avanse."

"Papye, Souplé."....

As always, there are a couple that throw me. One is a two-year-old who looks healthy, although her face doesn't look quite right, not quite normal, and she is the size of a six-month-old, and she can't walk yet....and she has a whopping heart murmur. Imagine someone with a lot of saliva in their throat, making a hissing sound, 60 times a minute. That is what her heart sounds like. I ask her mom if she has been hospitalized. Through the interpreter, I get that she was in Port-au-Prince hospital for a month after being born because mother had been thrashing so much in labor that she fell out of bed, and when she did that, she hit the baby's heart and made it not work well. They did an x-ray, but is was normal. I ask about an echocardiogram, then have to describe it through the interpreter, and it doesn't sound like one was done, but the doctor assured her that the heart would heal.

I don't know how to put together her story, and I don't know exactly what she was told, but this baby has a heart malformation and probably a genetic syndrome. She certainly didn't injure the heart with her thrashing, I don't know the next time Dr. Serge Geffrard, the pediatric cardiologist, with Project Haiti Heart, will be down seeing patients at HCM, but I take her name and information so that we can hook them up, giving the mother all kinds of precautions that I pray she will remember. and some vitamins, and some worms medicine.

"Avanse. Avanse."

"Papye, Souplé."....

At some point after three, the bus must have unloaded more children. At about 4, a 12 month old, who is not wearing a diaper, empties his bladder on my shirt and scrub bottoms. This is not altogether unheard of in my everyday life, but I usually have some way to clean up and a fresh set of scrubs on stand-by. I have neither today, and 25 patients still lined up to see me. I keep going. I see the kids with colds. The teens there for entertainment. I see them all, happy both that I am busy, and that they are not particularly ill. Everyone gets their meds. Everyone gets their vitamins, their worm medicine.

And mumps...Did I mention I saw a boy with mumps?

Doug

Wednesday, July 6, 2011 Simonette

Yeah about the delay in the blogs, The Internet connection has been playing a cruel game with me. It only seems to be active when I don't have time to sit down and blog. or when I am too tired. I guess the good news is that the events of this trip have not been as life and death compelling. I think I may have lucked into a "normal" mission trip. In Simonette, on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince, near Cite Soleil, the notoriously dangerous slum, we have our trip today. We came here in November. In fact, we were the last team here. There are ways to tell how poor a village is. In Haiti, dogs aren't often personal pets. They aren't eating Puppy Chow. They hang out in the village and live off scraps. The less food the people have the less scraps. the less scraps, the skinnier the dogs. There are some skinny dogs here. And red headed children. The hair color is significant. These are dark skinned people. The hair on the head is naturally dark. That color comes in the form of melanin. Melanin is dark from, or black, if there is enough of it. There is one absolute requirement in the body's production of melanin: protein. No protein, no melanin. In people of Irish descent who are redheaded, they simply lack the genes to produce melanin. Here, they lack the protein in the diet. It's called Kwashiorkor, or protein/calorie malnutrition. If you see a child with spindly legs, big belly, and red hair, they are not getting enough protein rich food. Fortunately, there is no child here in extremis, none that is starving to death, none with terrible infections. Most of the children, though have scabies, and we liberally coat them with permethrin cream, which kills the scabies mite. I get scabies, too. I have picked it up at some point this week. Permethrin cream is used liberally by the team tonight, as well.

Today, I find some recompense for the tragedy of our November trip. I diagnose a girl who has malaria, and she is not that sick yet. She will be cured. This won't come back to haunt another team down the line.

It is a bittersweet day. On the one hand, despite being hungry, the people here are not that ill. On the other hand, they are hungry, and today, we didn't bring any rice, which means the day is far less chaotic for us, but there will be empty bellies tonight for the children in the village.

Doug

Today, I find some recompense for the tragedy of our November trip. I diagnose a girl who has malaria, and she is not that sick yet. She will be cured. This won't come back to haunt another team down the line.

It is a bittersweet day. On the one hand, despite being hungry, the people here are not that ill. On the other hand, they are hungry, and today, we didn't bring any rice, which means the day is far less chaotic for us, but there will be empty bellies tonight for the children in the village.

Doug

Friday, July 8, 2011

July 5th Jacmel, Sud-Ouest, Haiti

Today we awoke at 3:20 to make for Jacmel. Jacmel itself has a population of about 150,000. Although it was spared the major damage of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake, it did sustain damage, including the collapse of half of its hospital. It was a long drive, 6 plus hours. On the way there, Ali, my baby, my 15-year-old baby, was tired, so she snuggled. In my experience, 15-year-olds are good for a quick hug if you are lucky, but not much into snuggling with their Daddys, so I was happy that she used my shoulder for a pillow. I could remember so clearly Ali as a newborn, sleeping in our bed. I would lie on my side, curled up around her, hyperaware of any movement she makes, not sleeping much, but content to protect and keep her. I feel much the same today. By leaning on her, I am not resting, but keeping her head from flopping forward. I am content.

Did I mention the trip is long? The scenery, though, that we pass through is amazing, up over the mountains. It is beautiful, a totally different world than the city below. This is where you can understand where terms like Mountains Beyond Mountains come from. The air in the mountains in chilly, upper 60's. the road is a rollicking 1 1/2 lanes of switchbacks, sheer drop-offs and blind turns. All taken at 50 mph. Dramamine is used liberally.

In Jacmel, proper, we buy rice at the market 80 pounds. We then travel to the church.

Haitian churches are not the same as the church you attend. They are open air. In the smaller towns and villages, they are spare. Although Jacmel is large, we are in what I guess could be called a suburb. Not a rich one. The timbers are all roughly hewn from the logs they started as. The post and beams and benches look like some Hollywood prop designer's exaggeration of rustic.

Today we are giving out rice. This means that we will be busy later on, once everyone has heard. These kids are cute. There are some ear infections, a lot of colds, a couple of kids with pneumonia, almost everyone has "vent fe mal" or stomach pain. Towards the afternoon, I get the teenagers who aren't really sick at all, they just want some entertainment. They goof off and are silly about my limited Kreyol, but we have a good time. Since none of these kids is particularly sick, I have time to reflect that a large part of my purpose here is to sift through all the healthy kids and find the ones who are truly ill. Without a lab. Without X-rays. So the ones who are in extremis are not difficult to spot. It's the ones that may be starting to get something serious that I am concerned about. Early malaria, early typhoid. I don't want to miss those. I may be the last to see them before they really get sick.

Then there is the two that will haunt me: the 9 month old who is the size of a 4 month old who otherwise looks well, and the 12 month old with the heart murmur that sounds abnormal, but otherwise looks well. At home, both would be referred, both would be worked up. Here, I talk to the mother of the 9 month old for about 20 minutes through the interpreter, talking about all the things I want her to watch for. With the 12 month old, I take the name and number down to put on the list for the next time the Pediatric Cardiologist comes down on a trip.

The rice is gone. We've seen about 100 patients, not too much of a workload, but with the drive starting at 4 am, by the time we get home at 8:30 pm, we are exhausted.

Did I mention the trip is long? The scenery, though, that we pass through is amazing, up over the mountains. It is beautiful, a totally different world than the city below. This is where you can understand where terms like Mountains Beyond Mountains come from. The air in the mountains in chilly, upper 60's. the road is a rollicking 1 1/2 lanes of switchbacks, sheer drop-offs and blind turns. All taken at 50 mph. Dramamine is used liberally.

In Jacmel, proper, we buy rice at the market 80 pounds. We then travel to the church.

Haitian churches are not the same as the church you attend. They are open air. In the smaller towns and villages, they are spare. Although Jacmel is large, we are in what I guess could be called a suburb. Not a rich one. The timbers are all roughly hewn from the logs they started as. The post and beams and benches look like some Hollywood prop designer's exaggeration of rustic.

Today we are giving out rice. This means that we will be busy later on, once everyone has heard. These kids are cute. There are some ear infections, a lot of colds, a couple of kids with pneumonia, almost everyone has "vent fe mal" or stomach pain. Towards the afternoon, I get the teenagers who aren't really sick at all, they just want some entertainment. They goof off and are silly about my limited Kreyol, but we have a good time. Since none of these kids is particularly sick, I have time to reflect that a large part of my purpose here is to sift through all the healthy kids and find the ones who are truly ill. Without a lab. Without X-rays. So the ones who are in extremis are not difficult to spot. It's the ones that may be starting to get something serious that I am concerned about. Early malaria, early typhoid. I don't want to miss those. I may be the last to see them before they really get sick.

Then there is the two that will haunt me: the 9 month old who is the size of a 4 month old who otherwise looks well, and the 12 month old with the heart murmur that sounds abnormal, but otherwise looks well. At home, both would be referred, both would be worked up. Here, I talk to the mother of the 9 month old for about 20 minutes through the interpreter, talking about all the things I want her to watch for. With the 12 month old, I take the name and number down to put on the list for the next time the Pediatric Cardiologist comes down on a trip.

The rice is gone. We've seen about 100 patients, not too much of a workload, but with the drive starting at 4 am, by the time we get home at 8:30 pm, we are exhausted.

Sunday, July 3, 2011

Made it, unpacked, culture shock

I forget how strange it is to step out into a Third World country the first time. To me, the chaos of making it through customs, the throng at the airport, the smell of charcoal smoke in the air--even the rubble and trash and dizzying bustle of traffic and people--is familiar, but there are a lot of heads on swivels. Haiti is different and shocking, especially Port-au-Prince. I notice the little things: how everyone is curious, unselfconsciously so, about us. Not in our face at all, but everyone takes a look at us, only the children shout out "Blan!". We are here. With all our baggage. The ventilator, a piece of equipment that is $30,000 new, is safe. We tour the campus of the Haitian Christian Mission, then we eat, beef stew. It's delicious with potatoes, plantains, and dumplings. I've already broken a food rule: I bought fried plaintain I'm Port-au-Prince from a street vendor. It was incredible. I think hotboil kills all germs ever, right? After lunch, we unpack and clean the pharmacy. The pharmacy is a mess. It takes us hours, then dinner, then we eat again: roasted chicken. After dinner, we meet as a team, talk about the next day, and everyone scatters for bed. Except Sabine and me. She finishes the pharmacy, and I reconstruct the ventilator. Then I blog. I'm falling asleep as I do it. I'll sleep under the stars tonight, clinic starts in the morning.

Doug

Doug

Saturday, July 2, 2011

Today is the day

Okay, so it's still late Friday night for me. I'm finally done packing. I got a ventilator today! I hope I won't have to use it, but I am glad it will be there. It is taking up all or part of 4 duffel bags, but it is totally worth it.

I guess I don't know how I am feeling right now. I am excited and a little nervous. My last two trips were very stressful and emotional. so now I'm drawn to my first trip when it was all new, and I felt so inspired. The first impression is always the lens through which you look. I want to see Haiti like I did that first time. I know Port -au-Prince will still be a wreck. I will look at it again through fresh eyes, or maybe eyes that remember what is was like when they were fresh. The voices and faces of those who have joined me in the past will again be with me. I wish they were there in body. That said, I am very excited about this team. Sabine will again be leading and has already done a great job, and I have my family here who will get to see what I have come to love, and a big, excited, Capital Region contingent. So maybe they can all help me see it anew. Last time I wnated to tell stories, I want this time to be about drawing the scene, bringing you here not only visually, but viscerally. That is what I will try to do this week.

As promised the team that will accompany us:

Julia Asmar -- Student

Quinn Ayres -- Med. Assistant

Alyssa Borchelt -- Nurse Assistant

Ali Boudreau -- Student

Doug Boudreau -- MD- Pediatrician

Jeanne Boudreau -- Arts

Melinda Dessieux -- Nutritionist

Sabine Dessieux -- FNP

Ashley Doyen -- RN-CC

Amanda Helton -- RN-CC

Molly Magoon -- RN-CC

Gracia Nabhane -- MD-Pulmonologist

Judy Njeri -- RN Student

Lindsay Otto -- RN-CC

Kelly Prenger -- RN-CC

Olwyn Ross -- RN- Wounds

Chache Lajwa!

Doug

Monday, June 20, 2011

Upcoming trip: July 2nd-10th, 2011