Doug

Gonaive is a little village to the northwest of Port au Prince, a two and a half hour drive. I have not been here since my first trip to Haiti, October 2009, prior to the earthquake. Memories tug at me as we drive to the village of Saint Marc and drive on further up. I remember a poor village, where many children were malnourished . I remember being relieved when I saw Gonaive has a school. A school means schoolchildren get to eat. This village has not been visited by a mission team since our last time here.

We arrive. It is a forgotten village, a poor village, and I hope things are not too desperate here. Living in this village is like careening down a twisty mountain road, mere inches from going over the edge, and there is nothing to stop the fall, no guardrail.

Guesly

Erika returns with her assessment: The patient’s cervix is 7 to 8 cm dilated and almost completely thinned out. This is her third pregnancy. I look around me in this dark cinder block church with primitive wiring for electricity powered by a generator. The roof is corrugated aluminum sheet held with sparse wooden trusses The church is dim with light creeping in from a few well crafted fenestrated cinder blocks. The floor is a mixture of dirt and large sharp rocks which remind me where I am with every step. I think we might have to deliver her here. I make my way to an unfinished alcove behind the altar. It is the only area that is semi-private.. As I enter the room, I see a women in her late 20’s to early 30’s lying on a oversize trash bag which covers most of her trunk on the unforgiving rock. Her feet and sandals are darkened to the color of the dirt; her dress is pulled up over her belly. She moans with each contraction. It has been almost five years since I finished residency , I know delivering children is far beyond the scope of medicine I want to practice. Haiti does not care about my preferences and brings unexpected and inconvenient challenges with each mission trip. This is Erika’s second trip to Haiti and already she knows to expect the unexpected. But it is not so much the unexpected that is the problem. The problem is that there is no system equipped to handle the unexpected. If we, the intermittent and temporary mission teams, are the best response, then the system is broken. To change the high morality and morbidity of newborns and their mothers, the whole system must be fixed.

“Dokte, dokte- nou gen yon maman ke vini avek yon tibebe ke mouri nan vant li!”* I am sitting in the dining room playing a game called Qurko with my sister Sabine and Ouyse, a family resident from Kansas City, when I hear the call of one of the translators. I spring to my feet, and grab Cory Miller, an OB-gyn resident from Columbia Missouri. We rush downstairs to find a women in the operating room, lying on the surgical table. At first glance, I can tell something is not right, something beyond the moans with every contraction.. Her appearance is off. Her face was swollen like someone suffering an allergic reaction, but I know that is not the case. The swelling is also encompassing her arms and legs. She is lethargic and remains still until a contraction stirs her to thrash and moan again. I asked her name and age. In Creole, she tells me she is 19 years old and 8 months pregnant. She continues to answer questions in a soft, anguished voice as I translate for Cory who does not speak Creole. We both notice her husband is not present in the room but waits outside in the lobby area. She explains that she lives in the mountains past a place called Fond Varette. As she speaks, I start to understand how difficult her journey has been. Fond Varette is a mountain where we often hold mobile clinics. The terrain to the small village is very unforgiving and painful. It has no mercy for people or vehicles. The road is very dusty because it runs along a dry riverbed. It has ruts due to erosion from repeated heavy rainfall and haphazard road construction. The drive itself is a slow climb on a road built to handle one vehicle but often carries three to four lanes of traffic. When I ride on it, I always hope I am on the vehicle closest to the mountain, not the vehicle on the outside where the edge falls off to a several thousand foot drop. No guardrail will arrest the fall. Traveling that road in the middle of the night in the back of a tap-tap is terrifying to imagine, even for someone who is not eight months pregnant. As I think this, she tells us her story.

On Friday, the mother developed a fever and noticed ther baby was not moving. The next day, she developed sudden abdominal pain,causing her to double over, and she began bleeding from her vagina. Her husband urged her to go to the hospital. This is their first baby; they just married a year ago. They went to see a local midwife, but she refused to see the mother. They waited. By Monday, the pain and contractions are unbearable. They make the harrowing trip down the mountain.

After Cory and I both assess her it was clear there is no fetal heart beat. Her unborn child will not have a chance to fight for his or her life. Our minds turn to treating her current potentially fatal medical condition. She arrives with severely elevated blood pressure and swelling. She had a condition called preeclampsia, and if it is not treated she could rapidly develop eclampsia which could endanger her life. Preeclampsia is a hypertensive syndrome that occurs in pregnant women after 20 weeks gestation consisting of new onset, persistent elevated blood pressure. Eclampsia is the progression of the disease process with initiation of seizure. I defer to Cory’s expertise concerning the treatment and management of this condition. My concern is whether an emergency c-section will be needed to remove the dead baby in her belly. Cory and I decide to awaken the surgical crew and Dr. Higgins, the general surgeon who practices in Kansas City. Dr. Cory and Dr. Higgins perform the surgery. Once the baby is delivered, it is clear he has not been alive for some time. Around the placenta is old clotted blood. The placenta has separated prematurely from the uterus, a condition called placental abruption. This condition is rapidly lethal for the baby and very dangerous for the mother. Her condition is not uncommon, and if recognized and treated, the risk to mother and baby can be minimized. That requires good pre-natal care which the patient failed to get because of location she lives, the scarcity of physicians, the lack of education, and a health system that only provides care to those who could afford to pay. Since eighty percent of Haitians are poor, all those pieces rarely fall into place, and this outcome is all too common.

Doug

We name the baby Esau. It was clear from the moment he is handed to me his earthly journey was over before his mother ever came down from the mountain. He is tiny, less than 5 pounds. He is limp. He has lividity in his skin, the blood pooling due to gravity after death. I listen to his heart, and this formality confirms what I already know. I wonder if he could have been saved in the US. I don’t know. I certainly have seen babies stillborn at my hospital. But the survival rate of a child living until the age of two is fifty times worse in Haiti than the US. Mothers are 100 times more likely to die in childbirth.

We pray over Esau, welcoming him into this world, and wishing him well on his journey out of it. That night he is buried next to David.

Guesly

We cannot have the baby here. I think this as I look around the rural Haitian church. There are no sterile instruments, only dental floss to tie off the umbilical cord. My mind drifts back to only eight hours ago when we had to tell a 19 year old mother that not only was her baby dead, but we had to have an emergency operation. We cannot deliver here. Doug, our pediatrician, concurs with this. I realize the pain of delivery would be far from the only pain she would suffer with no comfortable place for her to lay, increased risk for infection, and the possibility of unforeseen complications which could even lead to death of her unborn baby. I think if we were closer, I would take her to Fond Parisian where we have trained staff and emergency equipment. Even in Haiti, we can have a situation where the likelihood of survival can be improved, but we are several hours from the hospital, None of us did think she would make it. I can imagine her delivering driving eighty miles per hour in a street packed with cars, motorbikes, bicycles, and pedestrians. Fortunately, we are told of a location five minutes drive away with a trained midwife. clinic. Without a second thought I tell Erica to get the mother, and she and Sabine drive her to that clinic.

Haiti must change in this modern age. It cannot continue to operate in a fashion that does not respect or treasure human life.

Doug

Gonaive is better than I had hoped. We have a long, but good day. There are two or three very ill people, and we do what we can for them. In general, these people are managing. As Guesly says, it is hard to appreciate that Haiti, as a governmental system, is living up to its role as protector of the people, to provide that safety for those weak, in danger, and at risk. It is indeed hard to see where there is enough value given to human life. For now, though, this forgotten village is continuing on its road, on the edge, without a guardrail.

*"We have a mother that came with a baby that died in the womb"

Search This Blog

Monday, November 14, 2011

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Monday, November 07, 2011 -- Ghosts of Port au Prince

Doug

Today we travel to a church in Port au Prince for a mobile clinic. Guesly and I accompany a medical team from Bethel Church, in Washington. This is the first time I’ve actually worked in Port au Prince since the January 2010 trip, when we set up clinic at a school where the main building had collapsed, entombing close to 30 students. We worked there in the eerie wake of those lost but not quite gone children. Now we arrive at a resurrection of sorts. This church building was destroyed in the quake. It is, as are so many buildings in Port au Prince, in the process of being rebuilt. In this shell, I wonder, how many were lost? What ghosts still linger? I’m not talking about the fantastic, tortured shades of cinema. It’s the everyday ghosts. The memories that intrude. The old places, down in rubble. The rubble now cleared. The faces still fresh in the mind that will never be seen again. Every one a husband, a grandmother, a sister, a child. So many lost, so much loss. The scars that are everywhere--on the land, on the buildings, on the bodies. I still can see the haunted look on the faces of everyone we passed in the days after the quake. When I talk to survivors, “Where were you when it happened?” the look returns. The ghosts still just beneath the surface. Guesly and I will see that today.

Guesly

“Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” The old lady sits across from me in a makeshift church made of cinder block. Steel rebar sprouts from the ceiling and walls. This is our mobile clinic, this church where privacy is gives way to the children peeking through the many cracks in the walls. Again the patient says in “Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” Creole. Her statement brings me back to reality, the reality of being in Haiti again for another mission trip. This is the first time I am back in Port au Prince, working in a clinic since we were here after the earthquake. The images from the earthquake remain vividly in my mind, through the images from the TV screen and in images from my own memory after leading a medical team to help with relief efforts. I remember all the rubble from the crumbled buildings. I remember the sheer number of buildings destroyed, and I remember the sense of hopelessness in the Haitian people’s faces. Today, I see little remaining of the rubble. I see more normal activity, the hustle and bustle of life in Haiti, which would be considered completely chaotic for anybody living in the States or elsewhere but is welcome and comfortable here. After a few seconds that felt like several hours lost in my thoughts, I ask “Ki kote ou gen dolor, madam?” “Where do you hurt?” She explains in Creole that every day she has pain, tingling, and numbness down her left leg. She describes pain that has stolen her sleep and that grows worse below her knee. She says her pain started over a year and a half ago. As she speaks I begin to think of a laundry list of questions I need to ask to find exactly the source of her pain. When she is done talking, she patiently answers my questions as she sits, well dressed in her Sunday best, a white handkerchief wrapped over her head. Her facial expression appears fatigued like a person who has lived several hundred Sundays and has yielded to the hardship, poverty, gifts, and hopelessness that comes with being born in Haiti. .

After I have asked my questions to satisfy my need for information and develop my differential, I begin to examine her and the suspect area. Finally, I kindly ask her to lift her dress enough so I can see her leg and knee. What I see catches me completely by surprise. I should have thought of this in my differential, but my observation of her started with seeing her walk through the court yard with a considerable amount of large rocks strewn about like a river bed. Even I had difficulty maneuvering without spraining an ankle, but from what I saw she had no trouble walking. She was slow, but that is not uncommon for her age. I recall this as I am staring at what has appeared from under her dress. It is not her own leg. It looks completely different than her other one, and I realize it is artificial, prosthetic.

Her voce soft and gentle, she begins to talk about what people call in Haiti “the event.” ”When the event occurred on January 12, 2010, I was in my house when suddenly it shook and I fell, and the house fell, and I was trapped underneath the rubble…” She smiles to reassure me, but I see through it that she has lost more then her leg Her eyes glaze, and I sense that I have brought back a flood of painful memories that she would rather keep hidden deep in her subconscious as her left leg was hidden underneath her dress. As we talk, she explains that her lower leg was crushed, it was removed, gone, but some days she feels tingling and pain all the way down her leg to the ankle as if it was still there and had not been “cut off.” I place my head down for a second, again reliving the memories of my time spent after the earthquake.

I remember a little girl I saw, just 11 years old, whose father had argued that he did not want “ them” to cut his daughter's legs off so that she would never be whole. “Them” referred to the various foreign doctors that came to help with earthquake relief efforts whose efforts to saves lives meant amputating limbs from crush victims. The Haitian people equated seeing the foreign doctors to losing arms and legs. They had real fears in that time that seeing “them” would destroy their wholeness. The 11 year old’s leg was leg became infected after being crushed, and there were concerns that the infection could be make it way into her blood stream, which meant she lost her leg or lost her life. Either decision came with a terrible price. In the end the earthquake cost the daughter her leg, but not the family their daughter. I know this woman now sitting in front of me must have faced the same awful choice.

I explain to the patient she is experiencing what is called phantom pain. This could be a syndrome in itself as many people who had limbs amputated suffer from these symptoms. Patients often feel as though their leg is still present, causing them pain to the point of being debilitating. Phantom pain can be helped if the patient is placed on medication that decreases the pain signals generated from damaged nerves. She appears to be satisfied with my explanation and wonder about the medication. I explained to her that unfortunately I did not carry that medication with me and she would need to travel to Fond Parisen where the mission hospital and clinic has a limited amount. After some further discussion, I give her prescription for Tylenol as I did not have any narcotic with me and it is hard to find in Haiti. She says a polite thank you “doc” , and promises to try to go to the hospital in Fond. Fond Parisen is the home of the mission hospital I travel to while in Haiti. It is about an hour from the church in Port au Prince but could be 4 to 5 hours with traffic.

After my encounter I begin to think how far in time it seems since I was in Haiti to help treat earthquake victims, yet how is seems like yesterday to the Haitian people who were afflicted and who continue to seek treatment for their injures. I wonder if that little girl is suffering from similar symptoms and if she will seek treatment as my patient today. Already the world has forgotten or is forgetting about Haiti. The news is always looking for the next sensational story. But the people in Haiti cannot forget. They continue to suffer. Their lives are forever changed. The need for healing will surpass my time and my generation. Do not forget about Haiti as the need for help is just beginning.

Doug:

So much is better. So much has healed, but the scars, the ghosts persist. Phantom limb may be a good way to think of it. It’s as if the whole body of the people of Port au Prince has lost a limb. The body moves, the people move about and get along the best they can, but they still feel it, every day. They feel them, the ones they lost, the ones we lost, every day. It’s been a good, tiring clinic. We head back to Fond Parisien to regroup and restock, and leave the city to its ghosts.

Port au Prince, November 7, 2011

Today we travel to a church in Port au Prince for a mobile clinic. Guesly and I accompany a medical team from Bethel Church, in Washington. This is the first time I’ve actually worked in Port au Prince since the January 2010 trip, when we set up clinic at a school where the main building had collapsed, entombing close to 30 students. We worked there in the eerie wake of those lost but not quite gone children. Now we arrive at a resurrection of sorts. This church building was destroyed in the quake. It is, as are so many buildings in Port au Prince, in the process of being rebuilt. In this shell, I wonder, how many were lost? What ghosts still linger? I’m not talking about the fantastic, tortured shades of cinema. It’s the everyday ghosts. The memories that intrude. The old places, down in rubble. The rubble now cleared. The faces still fresh in the mind that will never be seen again. Every one a husband, a grandmother, a sister, a child. So many lost, so much loss. The scars that are everywhere--on the land, on the buildings, on the bodies. I still can see the haunted look on the faces of everyone we passed in the days after the quake. When I talk to survivors, “Where were you when it happened?” the look returns. The ghosts still just beneath the surface. Guesly and I will see that today.

Guesly

“Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” The old lady sits across from me in a makeshift church made of cinder block. Steel rebar sprouts from the ceiling and walls. This is our mobile clinic, this church where privacy is gives way to the children peeking through the many cracks in the walls. Again the patient says in “Doc mwen gen dolor nan pe’m.” Creole. Her statement brings me back to reality, the reality of being in Haiti again for another mission trip. This is the first time I am back in Port au Prince, working in a clinic since we were here after the earthquake. The images from the earthquake remain vividly in my mind, through the images from the TV screen and in images from my own memory after leading a medical team to help with relief efforts. I remember all the rubble from the crumbled buildings. I remember the sheer number of buildings destroyed, and I remember the sense of hopelessness in the Haitian people’s faces. Today, I see little remaining of the rubble. I see more normal activity, the hustle and bustle of life in Haiti, which would be considered completely chaotic for anybody living in the States or elsewhere but is welcome and comfortable here. After a few seconds that felt like several hours lost in my thoughts, I ask “Ki kote ou gen dolor, madam?” “Where do you hurt?” She explains in Creole that every day she has pain, tingling, and numbness down her left leg. She describes pain that has stolen her sleep and that grows worse below her knee. She says her pain started over a year and a half ago. As she speaks I begin to think of a laundry list of questions I need to ask to find exactly the source of her pain. When she is done talking, she patiently answers my questions as she sits, well dressed in her Sunday best, a white handkerchief wrapped over her head. Her facial expression appears fatigued like a person who has lived several hundred Sundays and has yielded to the hardship, poverty, gifts, and hopelessness that comes with being born in Haiti. .

After I have asked my questions to satisfy my need for information and develop my differential, I begin to examine her and the suspect area. Finally, I kindly ask her to lift her dress enough so I can see her leg and knee. What I see catches me completely by surprise. I should have thought of this in my differential, but my observation of her started with seeing her walk through the court yard with a considerable amount of large rocks strewn about like a river bed. Even I had difficulty maneuvering without spraining an ankle, but from what I saw she had no trouble walking. She was slow, but that is not uncommon for her age. I recall this as I am staring at what has appeared from under her dress. It is not her own leg. It looks completely different than her other one, and I realize it is artificial, prosthetic.

Her voce soft and gentle, she begins to talk about what people call in Haiti “the event.” ”When the event occurred on January 12, 2010, I was in my house when suddenly it shook and I fell, and the house fell, and I was trapped underneath the rubble…” She smiles to reassure me, but I see through it that she has lost more then her leg Her eyes glaze, and I sense that I have brought back a flood of painful memories that she would rather keep hidden deep in her subconscious as her left leg was hidden underneath her dress. As we talk, she explains that her lower leg was crushed, it was removed, gone, but some days she feels tingling and pain all the way down her leg to the ankle as if it was still there and had not been “cut off.” I place my head down for a second, again reliving the memories of my time spent after the earthquake.

I remember a little girl I saw, just 11 years old, whose father had argued that he did not want “ them” to cut his daughter's legs off so that she would never be whole. “Them” referred to the various foreign doctors that came to help with earthquake relief efforts whose efforts to saves lives meant amputating limbs from crush victims. The Haitian people equated seeing the foreign doctors to losing arms and legs. They had real fears in that time that seeing “them” would destroy their wholeness. The 11 year old’s leg was leg became infected after being crushed, and there were concerns that the infection could be make it way into her blood stream, which meant she lost her leg or lost her life. Either decision came with a terrible price. In the end the earthquake cost the daughter her leg, but not the family their daughter. I know this woman now sitting in front of me must have faced the same awful choice.

I explain to the patient she is experiencing what is called phantom pain. This could be a syndrome in itself as many people who had limbs amputated suffer from these symptoms. Patients often feel as though their leg is still present, causing them pain to the point of being debilitating. Phantom pain can be helped if the patient is placed on medication that decreases the pain signals generated from damaged nerves. She appears to be satisfied with my explanation and wonder about the medication. I explained to her that unfortunately I did not carry that medication with me and she would need to travel to Fond Parisen where the mission hospital and clinic has a limited amount. After some further discussion, I give her prescription for Tylenol as I did not have any narcotic with me and it is hard to find in Haiti. She says a polite thank you “doc” , and promises to try to go to the hospital in Fond. Fond Parisen is the home of the mission hospital I travel to while in Haiti. It is about an hour from the church in Port au Prince but could be 4 to 5 hours with traffic.

After my encounter I begin to think how far in time it seems since I was in Haiti to help treat earthquake victims, yet how is seems like yesterday to the Haitian people who were afflicted and who continue to seek treatment for their injures. I wonder if that little girl is suffering from similar symptoms and if she will seek treatment as my patient today. Already the world has forgotten or is forgetting about Haiti. The news is always looking for the next sensational story. But the people in Haiti cannot forget. They continue to suffer. Their lives are forever changed. The need for healing will surpass my time and my generation. Do not forget about Haiti as the need for help is just beginning.

Doug:

So much is better. So much has healed, but the scars, the ghosts persist. Phantom limb may be a good way to think of it. It’s as if the whole body of the people of Port au Prince has lost a limb. The body moves, the people move about and get along the best they can, but they still feel it, every day. They feel them, the ones they lost, the ones we lost, every day. It’s been a good, tiring clinic. We head back to Fond Parisien to regroup and restock, and leave the city to its ghosts.

Port au Prince, November 7, 2011

Monday, November 7, 2011

Landed and (hopefully) Grounded

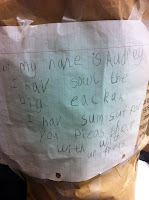

We arrive Sunday after a long travel day. Late, we are delayed in Miami, we land in darkness. We breeze through customs. I don't know if we are getting better at this, the wheels are used to being well greased, or my tolerance for the chaos is just higher. All the bags make it. Outside the airport, making the way to the vans, the darkness is a new experience. Port au Prince airport at night is eerie and vaguely threatening. I shrug it off, I wonder what I would think if it was my first time here. /the trip to Fond Parisien is quiet. I have time to think about the strange flow of events that have brought me back here again. I keep thinking back to an appointment I had last Thursday. It was a routine well check wit my patient Audrey, an 8 year old who I have seen since birth. She is delighted to see me, and she has brought a paper grocery bag with her. In it are many treasures: stuffed animals, books, bubbles, two boxes of macaroni and cheese, and various other small things that are important to an eight year old. She has printed a big note

"My name is Audrey. I have saw the Earthquake. I have some stuff for you. Please share with your friends." Almost two years ago, she was touched by the plight of the people of Haiti. At 6, she thought "what would I want, if I were in Haiti." So she gathered the things that make a six year old happy. And she saved them. She also collected some money and saved that. She was looking for some way to get it to Haitian children. She finally realized that I was going back to Haiti and brought it in to her appointment. I could barely read it in front of her without tears welling up. Just thinking about it now, I feel the same way. It's that purity of generosity, of a will to help, that is the wave that I have ridden, once again, to this place.

I raised a lot of money after the earthquake, and I've spent nearly all of it funding 5 mission trips, and it's not because I am a good fundraiser. I stink at it. I have a hard time asking people for money, so the money that has been donated came from people like Audrey, who still have Haiti on their hearts, even nearly two years later. I just had a family send me a check whose father had been a missionary to Haiti, and he had always wanted to share the experience with his family, but he dies before he could. So they are sending me along in his memory. In a way, then, he is with me. All the team members who have shared this mission previously are with me, as well.

So thank you, Audrey, and thank you everyone who continues to support us despite my ineptness in asking for it. I believe in what we are doing. The people who come with us are the wave riders, and you are the wave. This week, I want to make it worth it. I want to use Audrey's bag and everything in it in the best way possible.

Doug 11/6/2011

"My name is Audrey. I have saw the Earthquake. I have some stuff for you. Please share with your friends." Almost two years ago, she was touched by the plight of the people of Haiti. At 6, she thought "what would I want, if I were in Haiti." So she gathered the things that make a six year old happy. And she saved them. She also collected some money and saved that. She was looking for some way to get it to Haitian children. She finally realized that I was going back to Haiti and brought it in to her appointment. I could barely read it in front of her without tears welling up. Just thinking about it now, I feel the same way. It's that purity of generosity, of a will to help, that is the wave that I have ridden, once again, to this place.

I raised a lot of money after the earthquake, and I've spent nearly all of it funding 5 mission trips, and it's not because I am a good fundraiser. I stink at it. I have a hard time asking people for money, so the money that has been donated came from people like Audrey, who still have Haiti on their hearts, even nearly two years later. I just had a family send me a check whose father had been a missionary to Haiti, and he had always wanted to share the experience with his family, but he dies before he could. So they are sending me along in his memory. In a way, then, he is with me. All the team members who have shared this mission previously are with me, as well.

So thank you, Audrey, and thank you everyone who continues to support us despite my ineptness in asking for it. I believe in what we are doing. The people who come with us are the wave riders, and you are the wave. This week, I want to make it worth it. I want to use Audrey's bag and everything in it in the best way possible.

Doug 11/6/2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)